There are quite a few decisions to make with each crop you raise. One that takes more time to make, in my experience, is planting population.

With all the data you have on your farm from yields to fertility levels and more, dropping the same planting population on every acre of a field or even your whole farm just doesn’t make sense in 2022. I know as the combine gobbles up my corn, it’s showing 300 bushels in one zone and 200 in another. I don’t see consistent yields on every acre. I bet you don’t, either. With today’s technology, the varying populations has never been easier to do.

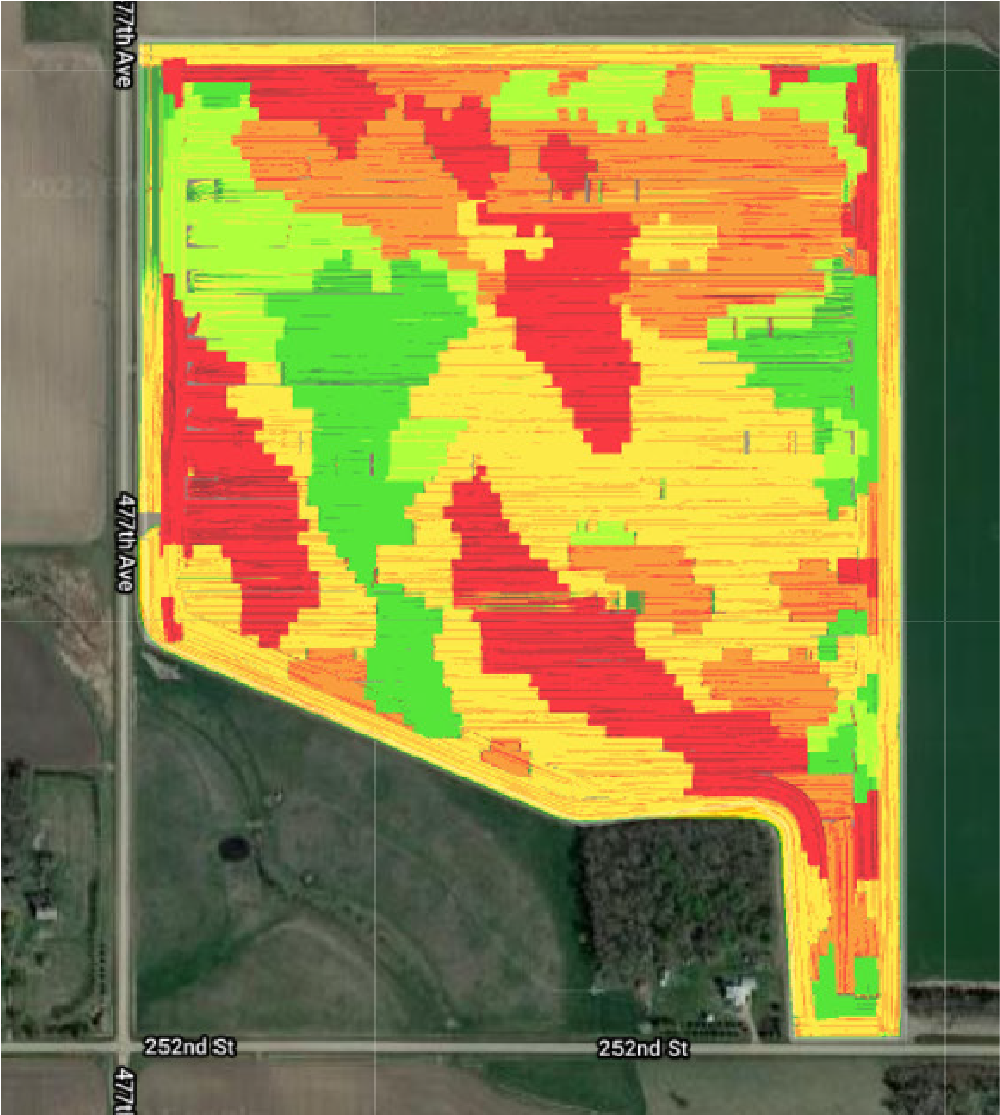

Variable rate population map from a field on the Hefty Farm planted to corn in 2021. Seeding rates in this field range from 28,000 (dark red) to 33,000 (dark green) seeds per acre.

What Population Do I Need?

The real question is, “What’s the lowest population I can run and still ensure I get every bushel of production?” I wish there was an easy answer that was always correct. There isn’t. However, planting a mix of populations is a great way to manage the risk of a drought year versus an ideal year or anything in between.

Corn: 7 to 10 Bushels Per 1000 Plants

I often use this example: If you plant 30,000 corn seeds per acre, how much yield should you expect? I would say somewhere between 210 and 300 bushels (which is 7 to 10 bushels per 1000 seeds). If you’re getting less than 210 bushels/acre, you are likely over-seeding. If you are getting more than 300 bushels, you may benefit from planting a higher population. Lower populations have significantly improved standability. If you’ve had plants fall over or even lean, chances are it’s not the fault of the hybrid. Improving potassium levels in the soil and lowering corn planting populations have mostly eliminated lodging issues for many farmers.

Soybeans: Higher Populations in the Worst

Areas and Lower Populations in the Best Areas Soybeans are the opposite of corn in terms of planting populations. We’ve had more success planting lower populations in the high fertility areas for a number of reasons. They tend to grow taller and bush out more with good fertility, and each plant puts on many more pods. Fewer seeds are needed to reach maximum yield. Also, a thinner population to start with allows more air movement through the canopy and results in less pressure from diseases like white mold. Higher populations have been more successful in the tough areas of fields. Quicker and thicker canopy chokes out weeds, puts more organic acids in the soil to lower high pHs and lessen the impact of Iron Deficiency Chlorosis, and a thick canopy helps conserve moisture in the hot, summer sun.

My Homework Assignment to You

This spring, work with your agronomist to try to dial in a variable planting population map for at least one or two of your fields. Be willing to have enough of a gap from high to low populations (for example: 26K, 30K, and 34K on corn) that you can see a difference. Match your data up with your yields this fall to see how it worked for you and if you should do this on your whole farm going forward.